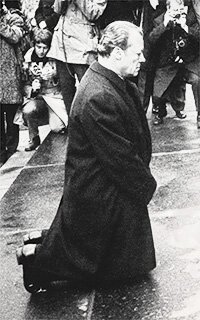

Some of you might remember. It was about 40 years ago… Willy Brandt, the then Chancellor of Germany, paid an official visit to Poland. During this trip, he did something that no one expected. He suddenly kneeled before the monument to the memory of the victims and remained on his knees for a minute, with his head bowed, apologizing in the name of the German state. He asked for forgiveness from the peoples of the world. TV channels across the world broadcast that moment. Willy Brandt apologized on behalf of the German people. By doing so, he glorified Germany. He helped the German people gain esteem.

Let us also remember that our neighbor Bulgaria’s Stalinist president Todor Zhivkov had decided to get rid of Bulgarian citizens of Turkish origin. In Turkey, Özal was in power back then. Turgut Özal had said “We shall welcome those people.” More than three thousand refugees arrived in Turkey. People were uprooted from their homeland. And today. It has been more than twenty years. Three years ago, the democratic parliament of Bulgaria, which is now a EU member, took a unanimous decision with 122 votes. The Bulgarian state apologized officially from Turkey, the Turkish people and those sent in exile back then. Only three parliamentarians abstained from the vote. There had been no demand for excuse, neither from Turkey, nor from anyone else. The Bulgarian parliament took a unilateral decision and apologized.

A similar event took place two years ago. In Germany, eight people of Turkish origin were murdered, but the incidents were covered up by the police. In time, the truth was revealed. It turned out that the murders were committed by Turkophobic neo-Nazi groups. The German Chancellor Angela Merkel did not attempt to deny the events. She assumed her responsibility. She apologized officially from the victimized Turkish families, on behalf of the German state.

The entire German people, that is 80 million individuals, observed a minute of silence in memory of the victims. Thereby, Angela Merkel glorified the German people and gained worldwide esteem. She also won hearts in Turkey.

Social peace is enjoyed exclusively by societies which have bravely come to terms with the dark moments in their past, by throwing aside the dark veil that covers the truth. That is, the call “Never again!” must reverberate in the streets, across the society, for peace and serenity, and the state must make an apology to preserve social cohesion.

Let us go back to the German and Bulgarian examples and ask ourselves the following: Why cannot we be as just and humane as Bulgarians or Germans?The official apologies by Germany and Bulgaria are just two examples. We have counted up to 150 such steps taken by states with a view to installing social peace and harmony.

This exhibition brings together 8 cases from Chile to the USA, from Australia to the UK, so that we do not see ourselves as a hapless people or think that our country is under “exceptional circumstances.”

We cannot step into the shoes of the general public, opinion leaders or decision makers. However, we would like to invite everyone to a process of rethinking.

With this digital version of our “Never Again! Apology and Coming to Terms with the Past” exhibition, it is our privilege to share the inspirational stories of those who made history by the amends they made and their acts of taking responsibility for the wrongdoings in their past.

July 2012: The initial idea of the exhibition began to take form with the discussions being carried out at the Open Society Foundation, as the conflicts, the peace-making processes and official apologies that took place in USA, Germany, France, Britain, Australia, Chile, Serbia and Bulgaria were all clinically reviewed.

September 2012: The Open Society Foundation and Anadolu Kültür came together to work on what would go on to become the “Never Again! Apology and Coming to Terms with the Past” exhibition, with the chief aim being to encourage people to rethink their past by drawing inspiration from cases with similar roots to the political issues being faced in Turkey.

November 2012: The Open Society Foundation and Anadolu Kültür staff, with the addition of curator Önder Özengi, began their several months long journey of arduous and meticulous work. With the academic counsel provided by Prof. Dr. Elazar Balkan, who is a globally renowned academic on the subjects of societies' and governments' steps towards restoring peace, over 150 apologies from recent history were taken into consideration and 8 historical cases were picked in the end.

A very vast scaled international research took place for the 8 cases which would, in turn, constitute the “Never Again! Apology and Coming to Terms with the Past” exhibition, which in turn garnered great interest from press and public alike upon its opening at Tophane / Depo in İstanbul on November 24th, 2013.

The research included findings, photos, documents, documentaries, videos and witness statements that best shed light on how the public faced the conflicts, mass killings and genocidal practices; how presidents and politicians apologised to their people and those who were wronged.

In the light of these selected cases, the exhibition began to be moulded into three stages; the event that caused the expectation of an apology in the first place, the struggle that took place to get to the stage of apology, and how the apology itself transpired, respectively. The exhibition also presented information about the truth commissions, international penalty courts, memorials and memory foundations, each an example seen in the individual cases included.

November 2013: In addition to the exhibition, the project later evolved into a book, which, published under the same name, aimed to provide a different insight on how the topic reflected on Turkey and around the world.

December 2013: We began working on building an online version of the exhibition to expand its reach and make its effect more lasting.

April 2014: With the 3 month collaboration between the Ocelott Interactive Communications Team and the exhibition staff as well as our curator, our digital exhibition came to life.

We aim to share the inspirational stories of those who made history by taking responsibility and making amends. With our now digital “Never Again! Apology and Coming to Terms with the Past” exhibition, our hope is that we are now one step closer to the answers.

“Never Again!: Apology and Coming to Terms with the Past”, is a joint project of Open Society Foundation and Anadolu Kültür.

Photographers and documentary film makers

Fred Hoare, Robert White, Marcelo Montecino, Paulo Slachevsky, Marcela Briones, Patricia Alfaro, Marco Ugarte, Behiç Günalan, Dusan Vranic, Irina Nedeva, Andrey Getov, Leslie Woodhead, Mick Csaky, Jon Jones

for sharing their photographs and documentaries.

Institutions

Mémoires d’Humanité (L’Humanité Gazetesi Arşivi / Archives of the newspaper L’Humanité); Ministère de la Défense - ecpad (Fransa Savunma Bakanlığı - ecpad Arşivi / French Ministry of Defence – ecpad Archive); INA (Ulusal Audiovisuel Enstitüsü, Fransa / National Audiovisual Institute, France); Getty Images Turkey; National Archives of Australia (Avustralya Devlet Arşivleri); Parliament of Australia (Avustralya Parlamentosu); The Library of Congress (ABD Kongre Kütüphanesi); Bundesarchiv (Alman Devlet Arşivi / The Federal Archives of Germany); Museum of Free Derry, Derry (Özgür Derry Müzesi, Derry); Birleşik Krallık Parlamentosu (UK Parliament); UTV Ltd, Belfast; Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, Santiago (Bellek ve İnsan Hakları Müzesi, Santiago / Museum of Memory and Human Rights, Santiago); Bulgaristan Devlet Ajansı Arşivi (Bulgaria State Agency Archives); Bulgar Ulusal Radyosu, Sofya (Bulgarian National Radio, Sofia); The Red House, Sofia; Lost Bulgaria, Sofia; Associated Press; Humanitarian Law Center, Belgrade (İnsani Hukuk Merkezi, Belgrad); Antelope Films; Directors Cut Films

for sharing their archives.

People

Murat Çelikkan, Meltem Aslan, Gökçe Tüylüoğlu, Özlem Yalçınkaya, Pelin Bardakçı, Aslı Çetinkaya, Irazca Geray, Urszula Wozniak, Gökhan Gençay, Christian Bergmann, José Manuel Rodríguez Leal, Adrian Kerr, Marijana Toma, Irina Nedeva, Peyo Tzankov Kolev, Tanıl Bora, Zeynep Moralı, Şengül Ertürk, Ahmet İnsel, Mithat Sancar, Ozan Erözden, Necati Sönmez, Burçak Muraben, Nazlı Gürlek, Hilal Ünal, Fahrettin Örenli, Muhsin Akgün

for all their generous help and support.

The Never Again! exhibition was first opened at Depo / Tophane and it stayed open between the dates October 25th and December 15th, 2013. The exhibition had a total of 22.413 visitors.

The exhibition’s next stops were the İzmir Kültürpark Art Gallery between May 2nd and 25th, as well as the Sümerpark Amed Art Gallery in Diyarbakır between June 4th and 29th.

Apology and Coming to

Terms with the Past

Apology as Historical Dialogue - Elazar Barkan

A Restorative Justice Approach between the Past and the Future - Turgut Tarhanlı

"I Apologize Before All People" - Tanıl Bora

Apology, Confrontation, Mourning - Yetvart Danzikyan

The Apology Dilemma for Uludere - Yıldız Ramazanoğlu

Let the State Apologize and the People Listen to Each Other - Karin Karakaşlı

Psycho-politics of Yüzleşme - Murat Paker

Genocide – Such a Difficult Word - Marijana Toma

Please choose a country.

Erica Harth (der.), Last Witnesses: Reflections on the Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

Greg Robinson, By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Leslie T. Hatamiya, “Institutions and Interest Groups: Understanding the Passage of the Japanese American Redress Bill”, When Sorry Isn’t Enough: The Controversy over Apologies and Reparations for Human Injustice içinde, Roy L. Brooks (der.), New York: New York University Press, 190-200, 1999.

Nancy F. Cott, Public Vows: A History of Marriage and the Nation içinde, Kindle Edisyonu, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Roger Daniels, “Redress Achieved: 1983-1990”, When Sorry Isn’t Enough: The Controversy over Apologies and Reparations for Human Injustice içinde, Roy L. Brooks (der.), New York: New York University Press, 189, 1999.

Roger Daniels, “Relocation, Redress, and the Report: A Historical Appraisal”, When Sorry Isn’t Enough: The Controversy over Apologies and Reparations for Human Injustice içinde, Roy L. Brooks (der.), New York: New York University Press, 183-186, 1999a.

Roy L. Brooks, “Japanese American Redress and the American Political Process: A Unique Achievement?”, When Sorry Isn’t Enough: The Controversy over Apologies and Reparations for Human Injustice içinde, Roy L. Brooks (der.), New York: New York University Press, 157-162,1999.

Sandra Taylor, “The Internment of Americans of Japanese Ancestry”, When Sorry Isn’t Enough: The Controversy over Apologies and Reparations for Human Injustice içinde, Roy L. Brooks (der.), New York: New York University Press, 165-168, 1999.

“Kniefall angemessen oder übertrieben?”, Der Spiegel 51: 27, 1970,

“The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising”, US Holocaust Memorial Museum,

Adam Krzeminski, “Der Kniefall”, Point. Portal Polsko-Niemiecki, Deutsch-Polnisches Portal.

Alexander Behrens, “‘Durfte Brandt knien?’ – Der Kniefall und der deutsch-polnische Vertrag”, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Online Akademie, 2010,

Elazar Barkan, Alexander Karn, “Group Apology as an Ethical Imperative”, Taking Wrongs Seriously: Apologies and Reconciliation içinde, Elazar Barkan ve Alexander Karn (der.), Stanford: Stanford University Press, 3-30, 2006.

Markus Kornprobst, Irredentism in European Politics: Argumentation, Compromise and Norms, Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Mithat Sancar, Geçmişle Hesaplaşma: Unutma Kültüründen Hatırlama Kültürüne, İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2007.

Ruti Teitel, “The Transitional Apology”, Taking Wrongs Seriously: Apologies and Reconciliation içinde, Elazar Barkan ve Alexander Karn (der.), Stanford: Stanford University Press, 101-114, 2006.

Valentin Rauer, “Symbols in Action: Willy Brandt’s Kneefall at the Warsaw Memorial”, Social Performance: Symbolic Action, Cultural Pragmatics, and Ritual içinde, Jeffrey C. Alexander, Bernhard Giesen ve Jason L. Mast (der.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 257-282, 2006.

Willy Brandt, My Life in Politics, New York: Viking, 1992.

A. Dirk Moses, “Official Apologies, Reconciliation, and Settler Colonialism: Australian Indigenous Alterity and Political Agency”, Citizenship Studies, 15:02, 145-159, 2011.

Danielle Celermajer, “The Apology in Australia: Re-covenanting the National Imaginary”, Taking Wrongs Seriously: Apologies and Reconciliation içinde, Elazar Barkan ve Alexander Karn (der.), Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006.

David Miller, “Holding Nations Responsible”, Ethics, 114 (January): 240-268, 2004.

Ali Dayıoğlu, Toplama Kampından Meclis’e: Bulgaristan’da Türk ve Müslüman Azınlığı, İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2005.

Huey Louis Kostanick, “Turkish Resettlement of Refugees from Bulgaria, 1950-1953”, Middle East Journal, 9(1): 41-52, 1955.

Julian Popov, “Bulgaria, Turks and the Politics of Apology”, Al Jazeera English, 26 Ocak, 2012,

Lilia Petkova, “The Ethnic Turks in Bulgaria: Social Integration and Impact in Bulgarian Turkish Relations, 1947-2000”, The Global Review of Ethnopolitics, 1(4): 42-59, 2002.

Svetla Dimitrova, “Bulgaria Apologises to Its Turks for ‘Revival Process’”, SE Times, (18 Ocak, 2012,

“Chirac attacks ‘history’ law”, The New York Times, 4 Ocak 2006,

“France recognises Algeria colonial suffering”, Al Jazeera, 20 Aralık 2012,

“Sarkozy in Algeria, calls French colonialism ‘profoundly unjust’” The New York Times, 3 Kasım 2007,

“Sarkozy tells Algeria: No apology for the past”, Reuters, 10 Temmuz,

Bruce Crumley, “Sarkozy confronted by Algerian anger”, Time, 3 Aralık 2007,

Claude Liauzu, “At war with France’s past”, Le Monde Diplomatique, Haziran 2005.

Clovis Casali, “Hollande says no apology for Algerian colonial past”,

Declaration on the Right to Insubordination in the War in Algeria (The Manifesto of the 121) 1960,

Gregory Viscusi, “Hollande Calls France’s Algerian Rule Brutal; No Apology”,

Jean Paul Sartre, “1961 Tarihli Baskıya Önsöz”, Frantz Fanon, Yeryüzünün Lanetlileri içinde, Şen Süer (çev.), İstanbul: Versus, 2005.

Jean-Luc Einaudi, Octobre 1961: un massacre à Paris, Paris: Fayard.

Julie Fette, “Apology and the Past in Contemporary France”, French Politics, Culture and Society, 26(2): 78-113, 2008.

Martin Evans, “French Resistance and the Algerian War”, History Today, 41(7), 1991,

Martin S. Alexander, Martin Evans, J.F.V. Keiger, “The ‘War without a Name’, the French Army and the Algerians: Recovering Experiences, Images and Testimonies”, The Algerian War and the French Army, 1954-62: Experiences, Images, Testimonies içinde, (der.) Martin S. Alexander, Martin Evans ve J.F.V. Keiger, New York: Macmillan, 1-39, 2002.

Mohammed Harbi, “Massacre in Algeria”, Le Monde Diplomatique, Mayıs 2005.

Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison, “Liberty, equality and colony”, Le Monde Diplomatique Haziran 2001.

Raphaëlle Branche, “The State, the Historians and the Algerian War in French Memory, 1994-2001”, Contemporary History on Trial: Europe since 1989 and the Role of the Expert Historian içinde, (der.) Harriet Jones, Kjell Östberg ve Nico Randeraad, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 159-173, 2007.

Robert Aldrich, “Colonial Past, Post-Colonial Present: History Wars French Style”, History Australia, 3(1): 1-10, 2006.

“İngiltere ‘Kanlı Pazar’ İçin 38 Yıl Sonra Özür Diledi”, bianet.org,

Brian Conway, Commemoration and Bloody Sunday: Pathways of Memory, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Eamonn McCann (der.) The Bloody Sunday Inquiry: The Families Speak Out, Londra: Pluto Press, 2005.

Patrick Joseph Hayes ve Jim Campbell, Bloody Sunday: Trauma, Pain and Politics, Londra: Pluto Press, 2005.

Elizabeth Jelin, “Silences, Visibility, and Agency: Ethnicity, Class, and Gender in Public Memorialization”, Identities in Transition: Challenges for Transitional Justice in Divided Societies içinde, Paige Arthur (der.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Ercan Eyüboğlu, Türkiye İşçi Partisi: Parlamento’da, 40. Yıl, İstanbul: Tüstav Yayınları, s. 15-19, 2006.

Ernesto Verdeja, Unchopping a Tree: Reconciliation in the Aftermath of Political Violence, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2009.

Supreme Decree No. 355, paragraph 9.

James Petras ve Morris Morley, The United States and Chile: Imperialism and the Overthrow of the Allende Government, New York: Monthly Review Press,1975.

James Smith, “Compromise with a Democratic Vision Takes Over Sunday in Chile”, Los Angeles Times, March 10, 1990.

Mario I. Aguilar, “The Disappeared and the Mesa de Diálogo in Chile 1999-2001: Searching for Those Who Never Grew Old”, Bulletin of Latin American Research, 21(3): 413-424, 2002.

Mark Obert, “Şili’nin En Büyük Stadyumunda Hayatını Geçiren Manuel Medina’dan ve Manuel Medina’ya Dair Anılar: Ulusal Stadyum’dan Sağ Çıkmak”, çev. Mithat Sancar, Birikim, 215: 99-107, Mart 2007.

Mithat Sancar, Geçmişle Hesaplaşma: Unutma Kültüründen Hatırlama Kültürüne, İstanbul: İletişim, 2007.

Patricio Aylwin, “Chile: Statement by President Aylwin on the Report of the National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation”, Transitional Justice: How Emerging Democracies Reckon with Former Regimes içinde, Neil J. Kritz (der.), Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 169-173, 1995.

Daniela Mehler, “Understanding Normative Gaps in Transitional Justice: The Serbian

Discourse on the Srebrenica Declaration 2010”, Journal of Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe, 11(4): 127-156, 2012.

İlhan Uzgel, “Balkanlarla İlişkiler”, Türk Dış Politikası, Cilt 2 içinde, Baskın Oran (der.), İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2001.

Jasna Dragovic-Soso, “Apologising for Srebrenica: The Declaration of the Serbian Parliament, the European Union and the Politics of Compromise”, East European Politics, 28(2): 163-179, 2012.

Jelena Obradovic-Wochnik, “Knowledge, Acknowledgement and Denial in Serbia’s Response to the Srebrenica Massacre”, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 17(1): 61-74, 2009.

Marjina Toma, “Genocide: Such a Difficult Word”, bu kitapta, 2013.

Olivera Simic ve Kathleen Daly, “ ‘One Pair of Shoes, One Life’: Steps towards Accountability for Genocide in Srebrenica”, The International Journal of Transitional Justice, 5: 477-491, 2011.

Remembrance and Reconciliation, edited by Robert Gildert and Dennis Rothermel, Rodopi, 2011.

The Age of Apology: Facing up to the Past, edited by Mark Gibney et.al., University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Forgiveness: A Philosophical Exploration, Charles L. Griswold, Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies, John Paul Lederach, United States Inst of Peace Press, 1997.

Taking Wrongs Seriously: Apologies and Reconciliation, edited by Elazar Barkan and Alexander Karn, Stanford University Press, 2006.

The Guilt of Nations: Restitution and Negotiating Historical Injustices, Elazar Barkan, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

When Sorry isn’t Enough: The Controversy over Apologies and Reperations for Human Injustice, Roy L. Brooks, NYU Press, 1999.

Reconciliation in Divided Societies: Finding Common Ground, Erin Daly and Jeremy Sarkin, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Closing the Books: Transitional Justice in Historical Perspective, Jon Elster, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Unsettling Accounts: Neither Truth nor Reconciliation in Confessions of State Violence, Leigh A. Payne, Duke University Press, 2008.

Mea Culpa: A Sociology of Apology and Reconciliation, Nicholas Tavuchis, Stanford University Press, 1991.

Political Reconciliation, Andrew Schaap, Taylor and Francis, 2012.

The Politics of Official Apologies, Melissa Nobles, Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Reconciliation(s): Transitional Justice in Postconflict Societies, edited by Joanna R. Quinn, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009.

Taking Responsibility for the Past: Reparation and Historical Justice, Janna Thompson, Polity Press, 2003.

Sorry States: Apologies in International Politics, Jennifer Lind, Cornell University Press, 2010.

I was wrong: The Meaning of Apologies, Nick Smith, Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Reconciliation After Violent Conflict: A Handbook, IDEA, 2003.

Geçmişle Hesaplaşma: Unutma Kültüründen Hatırlama Kültürüne, Mithat Sancar, İletişim Yayınları, 2007.

The spirits that were called the Bloody Sunday inquiry and the reconciliation process in Northern Ireland / Katharina Ploss, 2006, Sanat ve Sosyal Bilimler Fakültesi, master tezi, tez danışmanı Esra Çuhadar Gürkaynak.

Making Peace with the Past?: Memory, Trauma and the Irish Troubles, Graham Dawson, Manchester University Press, 2007.

The Turks of Bulgaria: The History, Culture and Political Fate of a Minority, Kemal Karpat, University of Wisconsin Press, 1991.

Turkey’s Neighborhood, edited by Mustafa Kibaroğlu, Foreign Policy Institute, 2008.

“When sorry isn’t good enough: Official remembrance and reconciliation in Australia”, Damien Short, Memory Studies, 5(3): 293-304, July 2012.

“Report on Redress: The Japanese American Internment”, Eric K.Yamamoto and Liann Ebesugawa // article used in The Handbook of Reperations, edited by Pablo De Greiff, Oxford University Press, 2008.

Divided Memory: The Nazi Past in the Two Germanys, Jeffrey Herf, Harvard University Press, 1997.

“Hakikat, Özürler ve tazminatlar”, Immanuel Wallerstein:

“Requests and Apologies: A Cross-Cultural Study of Speech Act Realization Patterns”

“Dünyada Özür Politikaları ve Türkiye”, Adnan Ekşigil, Birikim, no. 240, 2009.

“Geçmişle Hesaplaşmak: ‘Söyledim ve Vicdanımı Kurtardım’dan Ötesi”, Tanil Bora, Birikim, no. 248 (Geçmişle Hesaplaşma Kolay mı? sayısı), 2009.

“Tarihle Yüzleşme”, Taner Akçam, Birikim, no. 193-194 (Bir Zamanlar Ermeniler vardı!.. sayısı), 2005.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)

The Museum of Memory and Human Rights

The Museum of Free Derry

Bloody Sunday Inquiry

Women in Black

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The National Sorry Day Committee (NSDC)

The ‘Stolen Generations’ Testimonies’ project

Sorry Books

Bloody Sunday March Committee

WOMEN OF SREBRENICA

Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973

Making the History of 1989

The Library of the National Statistical Institute – Bulgaria

Lost Bulgaria

The National Archives of Australia

Jewish Virtual Library

The Holocaust History Project

The Library of Congress

The Federal Archives

Truth and Reconciliation Commissions

The United States Institute of Peace (USIP)

Hakikat Adalet Hafıza Merkezi

Our exhibition featured a “Sorry Book” for all our visitors to express their thoughts.

The visuals below are examples taken from that book.

Your thoughts are important to us. If you have anything you would like to share, please fill out the form below.

Japanese Americans were subjected to discriminatory practices ever since they settled in the USA. Naturalization Act of 1790 granted the right to American citizenship only to free white persons which put the immigrants from Japan in a difficult position. In time, African Americans also acquired the right to citizenship but the Asian immigrants could not benefit from these achievements for a long time. Tensions between the USA and Japan in the aftermath of the First World War escalated with Japan's invasion of Manchuria in 1931. Tipping point of these tensions focused on the Pacific Ocean was the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941 that started the war between the two countries. Long before the USA declared war FBI had already prepared lists of Japanese suspects in the country. Following the Pearl Harbor raid, these people namely Buddhist priests, journalists and teachers were put under surveillance.

Executive Order 9066 signed by President Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, bestowed the Minister of War with the authority of declaring certain areas as military zones from which any or all persons may be excluded. In line with this authority, Internment Camps were established in the states of California, Arkansas, Arizona, Idaho, Wyoming, Utah and Colorado. In these camps, where constitutional citizenship rights were suspended, soldiers imprisoned 120,000 Japanese people, 77,000 of whom were American citizens. In 1980 President Jimmy Carter signed the law for the establishment of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) in Congress. In 1983 the Commission published a report of recommendations calling for the Congress to officially apologize for the wrongs committed and pay reparations to the survivors.

The Civil Liberties Act signed in 1988 by President Ronald Reagan paved the way for the reparations to be paid to the victims. On December 7, 1991 on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack, President George H. W. Bush wrote a letter of apology which was sent to the surviving Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in the camps. President Clinton also published a letter on October 1, 1993 apologizing to the Japanese Americans for their sufferings.

During their period of rule the Nazis killed approximately 6 million people, the vast majority being Jews.

Prior the Second World War, in all invaded territories Germans had adopted the policy of establishing ghettos wherein Jews were segregated from the society and stripped off their constitutional citizenship status. Between 1941-43 Jews living in the ghettos had created close to a hundred resistance groups. The most resounding resistance organized by these groups was the resistance in Warsaw Ghetto. From this isolation area, which by the summer of 1942 was filled with close to 500 thousand people, around 300 thousand Jews were taken and sent to the extermination camp in Treblinka. The ensuing resistance in the Ghetto was able to hold out for one month.

During the first post-war years in Germany, the Nazi past did not want to be remembered. By 1960s, Federal Germany was being shaken with demonstrations that dared question this tainted history. Youth organizations of 1968 were starting new debates, demanding a genuine disclosure of that which underlay the Nazi mentality. Amidst the claims of transitioning to democracy, it had emerged as sine qua non of the demand for social democracy to expose the Nazis still on active duty in numerous branches of bureaucracy and the secret service, and question the mass support that carried Nazis to power in the first place. Through these struggles the past was raked up and it was acknowledged that genocide had been committed.

The aforementioned process of coming to terms with the past continued, spread over the years. One of the most significant moments of this process took place in Poland, where Federal Germany Chancellor Willy Brandt had gone to sign the Treaty of Warsaw as an indication of Germany’s rapprochement with Eastern Bloc countries and especially Poland. On December 7, 1970, during his visit to the monument built in memory of the people killed by Nazis in the Warsaw Jewish Ghetto, at a completely unexpected moment Brandt knelt on his knees before the monument and waited in silence.

Brandt’s gesture of apology went down in history as a turning point in coming to terms with the past. Brandt was granted the Nobel Peace Prize in 1971 for his works in the service of peace.

German state officials apologized from Israel and the Jewish people multiple times, and Germany paid reparations to Israel and the Holocaust survivors.

Australia was colonized by Britain towards the end of the 18th century. As of this date, the population of the native people shrank rapidly. The colonial administration that invaded the continent disregarded peoples‘ cultural values and accumulations and instead chose to assimilate the native “elements“ of the invaded lands. One of the methods employed in line with this objective was the integration propaganda. It was the forced separation of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families. These children torn from their families would later be known as the “Stolen Generations“.

The “Protection and Management of Aboriginal Natives“ act passed in 1869 had established complete control over every detail of Aboriginals‘ lives including where to live, whom to marry or how to farm their land. Aboriginal children were placed in missionary dormitories where they received the “necessary“ training to serve the white families that they would later be given to. It is estimated that through 1869-1969 one out of every three Aboriginal children, that is around 100 thousand children, were taken from their own families.

The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission started an investigation into the children taken from their families, and in 1997 released a report on the “National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families“. This report titled Bringing them Home addressed in detail the racist and colonialist practices that were continued until the 1970s.

The Commission‘s demand for an official apology was partially met and in 2001 all state parliaments published texts of apology for the “Stolen Generations“. The Federal government on the other hand, due to the Prime Minister John Howard‘s insistence, refused to apologize on grounds that in practice peace had been instituted. On the path to apology in Australia, the civil society that organized campaigns such as the National Sorry Day, Sorry Book and Journey of Healing played an extremely important role.

With the Labor Party victory in the February 2008 elections, Kevin Rudd became prime minister and made an official apology to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In his apology speech he put an end to the racist, colonialist settler politics of the past and emphasized the vision for a new future that embraces indigenous and non-indigenous peoples.

Following the official recognition of new Bulgaria by the Ottomans in 1909, Istanbul Protocol was signed between the two states guaranteeing the rights of the Muslim Turkish minority in Bulgaria. The minorities whose rights were expanded with the 1913 Treaty of Constantinople and 1919 Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine were able to continue their existence in Bulgaria without confronting any adversity.

Todor Zhivkov, who came to power in 1954, proceeded to change the constitution to the detriment of minorities as of 1971. Policies of the “Process of Rebirth“ put in effect in 1984 launched the “hard assimilation“ era manifested with arrests, exiles and forced labor practices. All Turkish names were changed to Bulgarian ones. It was prohibited to speak Turkish in public spaces, workplaces and schools. Among the bans were daily prayers, circumcision, as well as Islamic wedding and funeral rites. Turkish minority responded to the government“s sanctions by organizing a resistance. In 1985, a secret organization led by Ahmet Doğan and called the Turkish National Liberation Movement (BTMKH) was founded in Varna. This movement constituted the origin of the Rights and Freedoms Movement that later organized legally and is currently a coalition partner of the present government. Around 140 Turkish demonstrators lost their lives in the organized protests and campaigns. In 1989, 360 thousand Bulgarian citizens of Turkish descent had to immigrate to Turkey; this was the largest mandatory mass migration in Europe since the Second World War.

As a result of the ever growing reactions, Zhivkov had to resign in 1989 and was replaced by Mladenov who brought an end to the assimilation politics. Improvement of policies regarding the Turkish minority played a significant role in Bulgaria“s European Commission and European Union memberships and the efforts to amend relations with Turkey.

Bulgarian Parliamentary Committee of Human Rights and Religious Freedoms declared that Bulgarian citizens of Turkish descent were displaced with the aim of ethnic cleansing and called for the perpetrators to be punished.

An official declaration of apology was adopted in the parliament on January 11, 2013. In the declaration, the practices that the Turkish minority was subjected to in the recent past were defined as “ethnical cleansing“.

The Algerian War of 1954-62, wherein severe rights violations and breaches of international humanitarian law of war were committed in cold blood, has an important place in the history of French colonialism.

France invaded Algeria in 1830 and gave it a constitutional status which opened the entire land to the French settlers. Due to its constitutional status Algeria had an exceptional position within the overseas French territory. However, the status of the people here was that of colony subjects rather than citizens. Obtaining citizenship status was subject to certain conditions such as pledging not to adhere to sharia laws. French colonialism had collapsed the social and economic infrastructure of Algeria; unemployment and poverty was widespread. Impoverished Algerians had no choice but to immigrate to France in masses.

The National Liberation Front (FLN) was founded in 1954. FLN had the capacity to implement all methods of struggle to reach its goal of independence and was organizing urban guerrilla actions as well as peaceful demonstrations. The legitimacy FLN attained among the people made the masses, which supported the Algerian people’s struggle, take to the streets also in France. On October 17, 1961 the protest attended by 30,000 demonstrators in Paris was attacked by the French police who killed around 200 protestors who were beaten to death or thrown in the Seine River and drowned. The dirty war tactics of France gained legitimacy for FLN in the international platforms. In 1959, General De Gaulle opened to discussion Algeria’s right to self-determination. The talks between FLN and the French army were started and as a result of the negotiations the Evian Accords was signed in 1962. In line with the Accords, Algeria’s colonial status was declared defunct, and Algerians gained the right to self-determination. However, neither the one million Algerians killed during the war nor the war crimes committed by France were confronted with. The notion of establishing inquiry commissions to investigate the Algerian War did not come to the agenda until 1990s. In order to keep the memory of war crimes alive, a group of Algerian immigrants organized demonstrations in 1991 calling attention to the ìduty to rememberî.

Prior his visit to Algeria in 2007, President Nicolas Sarkozy said that the French presence in Algeria caused a lot of sufferings, and that colonialism was against the core values of France, but he did not take responsibility for the war crimes. In 2012, President François Hollande described the colonization of Algeria as “brutal and unjust” and said that he recognizes the sufferings inflicted by colonialism; but he too refrained from making an apology.

On January 30, 1972, a march was organized in the Derry city of Northern Ireland attended by around 20 thousand people. Supported by the British army the government had long been suppressing opposition of all kinds, and it was the government“s 1971 decision to ban all marches and parades that lit the fuse of this demonstration. Upon this ban, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) made a call to defend the right to peaceful protests. Demonstrators gathered in the Derry city center on Sunday, January 30 came face to face with the army forces; soldiers opened random fire on the crowd and 14 people lost their lives. For the Irish people this day would go down in history as “Bloody Sunday“.

Bloody Sunday became the symbol of the violent suppression of Irish struggle for freedom passed on from one generation to the next.

In order to subdue the reactions to the event, a court was established under the supervision of the British administration. This court for show headed by Lord Widgery did not even dare convene in Derry; testimonies of eye witnesses were not taken into consideration and the military personnel were acquitted. This process led to the further escalation of conflicts in Northern Ireland. While NICRA“s passive resistance lost blood, IRA became the legitimate representative of the Catholic Irish; a total of 3,673 people died in the conflicts that lasted more than thirty years.

IRA“s ceasefire in 1994 followed by the Belfast Agreement signed between the British government and IRA in 1998 created a peaceful environment wherein the official discourse on Bloody Sunday would been questioned. With the momentum gained by broad-based democratic campaigns such as the Bloody Sunday Justice Campaign, Prime Minister Tony Blair announced that a new inquiry into the events would be opened. The peace process contributed to the investigation, which in turn along with the ensuing apology contributed to the peace process. The “Saville Inquiry

The “Saville Inquiry“ chaired by Lord Saville became the most comprehensive inquiry in the history of Britain. The report published on June 15, 2010 established that the soldiers gave no warning before opening fire at the crowd, that they were under no attack whatsoever, and that some protestors were shot in the back indicating that they were trying to run away. It was the Prime Minister of the time David Cameron who expressed the apology in the parliament, one that was awaited by the people of Northern Ireland for the past 38 years.

The September 4, 1970 presidential elections in Chile marked a first in the history of South America: Left-socialists united under the roof of the Unidad Popular coalition led by Salvador Allende, and came to power through democratic elections. A new socialist construction period was thus launched in the country. Conservative powers that wanted to bring end to this state of affairs mobilized with the involvement of CIA and the financial support of the USA. The “Holy Alliance“ settled on the method of military coup in order to block the Unidad Popular that had come out victorious from the 1973 elections as well.

On September 11, 1973 the military junta led by General Pinochet gave an ultimatum to the government to resign within twenty four hours. Allende and his friends did not succumb. Army forces that bombed the Presidential Palace killed Allende on the second day of the coup. The parliament was dissolved and a mass scale manhunt was started across Chile. Thousands of people were taken under custody, put through violent tortures and brutally massacred in the operations carried out by the death squads. Military dictatorship took it upon itself to extinguish any and every center of opposition. A series of economic decisions were adopted for integration with international capitalism. However, the violations of the military junta continued to stir reactions across the world. A referendum was held in 1988 for Chile“s de facto ruler Pinochet to remain in office for another eight years, and despite the oppression 55.99% of the people voted “no“.

Christian Democrat Patricio Aylwin, who became the next president after Pinochet in 1990, aimed to soften the coup regime and build a bourgeois democracy. To this end he first had to expose the severe crimes against humanity committed during the coup years. Thus, with Aylwin“s directive the National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation was established with the mandate of investigating the rights violations. In frame of the 3,400 cases it investigated, the Commission established that the army and the government forces were responsible for 95% of the rights violations committed during the coup era. Speaking at the Santiago Stadium, which was used as a torture and massacre site during the first days of the coup, Aylwin promised that human dignity would never again be violated in Chile, and later in his televised speech on March 19, 1991 he officially apologized to the people of Chile. It was the struggle of the Chilean people and foremost the victims“ loved ones that brought about this apology.

In 1990s with the dissolution of Yugoslavia, religious-nationalist movements started to rise among the different ethnic communities that constituted the federation and voice demands for independence. Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia and Bosnia-Herzegovina declared independence one after another. On March 3, 1992 the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina, where Muslim Bosniaks and Orthodox Serbs constituted the majority of the population, declared independence; thereupon Bosnian Serbs founded the Republika Srpska. Bosnia-Herzegovina was recognized by the European Union and the USA however the Bosnian Serbs were objecting to the decision of independence. Supported by the President of Serbia Slobodan Milosevic and the Yugoslav army, Bosnian Serb forces declared war against Bosnia-Herzegovina on grounds of establishing the unity of Serbian territory. The Bosnia-Herzegovina war lasted four years; during the war that reached its most intense point in 1995, nearly 100,000 people lost their lives, 2 million people were displaced.

Following the Serbian army“s four years long siege of Bosnia-Herzegovina“s capital Sarajevo, Bosnian Muslims started to escape to areas under United Nations protection. In the summer of 1995, a horrid atrocity was committed in Srebrenica, which was under the protection of UN soldiers as a town where disarmed Bosniaks could take refuge. The town declared as a “safe haven“ by the UN was besieged and despite the presence of Dutch UN peacekeeping soldiers was captured by the Serbian paramilitary forces known as the “Scorpions“. In the course of a few days the Scorpions killed over 8,000 Bosniak men. The killed were buried in mass graves. Bosnians were subjected to tortures and inhumane treatments in the concentration camps

Decisions of the international courts and the EU were influential in Serbia accepting its responsibilities with regards the Srebrenica massacre. In 2009 the European Parliament adopted a resolution on Srebrenica, reiterating the full cooperation with International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) as a requirement for the EU integration of countries in Western Balkans. Both the truths unveiled by courts and the initiatives of EU were forcing Serbia“s hand to confront with its own past. The democratic opposition was also pressuring the political power to recognize the verdict of genocide.

Through the efforts of President Boris Tadic, on March 31, 2010, the Serbian Parliament adopted the declaration “Condemning the Crime in Srebrenica“. In the apology issued for the Srebrenica massacre, the events that took place were not described as genocide, and no reparations were paid to the victims. Both the ICTY and the local criminal courts fell short of punishing the perpetrators.

The September 11 attacks and developments immediately thereafter can be considered a milestone with regards the neoliberal “national security states”. 9/11 attacks caused the existing “national security” discourses to be reshaped with discourses of “antiterrorism”. A new and very complicated era has been embarked wherein if it is a matter of “terror” all fundamental rights and freedoms and primarily the right to fair trial can be suspended; furthermore this is the case not only in the USA but across the globe. USA’s “Guantanamo Camp” in Cuba came into service as an exceptional venue of the modern legal system. The Guantanamo prison, where the relevancy of crime and punishment has become obsolete and the time and more importantly the alleged crimes with which the imprisoned will be tried are ambiguous, is in fact a concentration camp since law here is nullified. Muslim minorities in the USA are also potential suspects who might be locked up in this camp any moment. However, the USA did not put this concentration camp into force upon the 9/11 attacks, the starting point of this practice dates a long way back. After Pearl Harbor, the Japanese Americans living in the USA were subjected to a variety of discriminatory treatments, stripped of their citizenship rights, and deprived of their freedom by being locked up in concentration camps.

Discriminatory practices against Japanese Americans correspond to the period they settled in the USA. Naturalization Act of 1790 granted the right to American citizenship only to “free white persons”. Democracy would advance step by step, influenced also by social struggles, and the right to citizenship would gradually expand to include blacks and slaves as well. However, the Japanese who had to immigrate to the USA were falling victim to this notorious law, they were either not recognized as legal citizens or their entry to the country was prevented from the start at the borders. The Japanese immigrants (Issei) in 1880s were the last group of immigrants who would be discriminated by being denied the right of naturalization. Nonetheless, another unfortunate situation was awaiting the Japanese Americans in the near future. Following Japan’s defeat of Russia in 1905, the term “yellow peril” was coined across the world implying the Japanese. Before long this discourse started to affect the Japanese Americans’ daily lives. The Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907 signed between the Japanese and American governments prohibited the migration of unqualified Japanese to the USA. In 1913, immigrants’ right to purchase land was repealed. Most Japanese Americans tried to overcome this situation by purchasing land in the name of their children. Again during this period, in eight states it was illegal for whites to marry the Japanese or the Chinese. Full-fledged discriminations were committed wrapped in this or that justification.

Meanwhile the real danger would present itself after the First World War which was to break out a year later. In 1920s the American navy decided that a final war in the Pacific Ocean was inevitable. USA started to prepare for battle against Japan. The National Origins Act of 1924, which would remain in effect until the 1965 Immigration and Nationalization Act, introduced severe restrictions on immigration to the USA from various countries including Japan but this time with justifications different from the ones coined in 1907. Along with Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the start of the Pacific War, American public opinion was rapidly turning against the Japanese. During the war years most Japanese Americans were living in big cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle or in reclusive rural communities.

On December 7, 1941 Japan launched a surprise air attack on the American Naval Base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, killing around 2.400 people. Prior the attack, FBI had already prepared lists of community leaders deemed to be “dangerous” such as Buddhist priests, newspaper editors and Japanese teachers on the West Coast. Upon the attack these people were immediately arrested and imprisoned in remote places in Montana and North Dakota. Neither they nor their families had any idea as to where they were taken. A month went by in such an uncertainty. In the meantime military officials such as Colonel Karl Bendetsen and General John DeWitt convinced President Franklin D. Roosevelt to banish all Japanese people. However, President Roosevelt had already asked Curtis Munson to prepare a special report on the same subject of Japanese Americans who were deemed “dangerous”. Unlike the allegations of FBI, this report had concluded that Japanese Americans posed no threat whatsoever. Ministry of Justice was at first opposed to the soldiers’ recommendations but the FBI was adamant. Furthermore FBI was claiming that it would handle the possible problems that could arise. The political polemics and strife between power blocks developed in favor of FBI and lit the fuse of the process wherein Japanese American citizens would be rounded up and imprisoned in concentration camps.

On February 19, 1942, about two months after Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed the “Executive Order 9066”. The order bestowed the Minister of War with the authority of declaring certain areas as military zones “from which any or all persons may be excluded”. The Order did not specify the preconditions for starting criminal investigations against the accused. As the Order went into effect, the Japanese Americans living in the West Coast and southern Arizona, which were declared military zones, were forced to hastily store or sell their possessions and properties. At first, Assembly Centers were established in racetracks and fairgrounds. Later a total of ten Internment Camps were established, two each in California, Arkansas and Arizona and one each in Idaho, Wyoming, Utah and Colorado. The detained Japanese Americans were rounded up in the camps. Before long 120.000 Japanese, 77.000 of whom were American citizens, were imprisoned in internment camps based on military directives –though the Order itself did not directly target them.

Assembly Centers were run by the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA). The detainees were deprived of their right to fair trial. The camps consisted of tar paper barracks of one small room for each family. Some detainees were able to leave the camp as seasonal workers. Similarly students, who could find schools willing to admit them, were able to study at universities in the East Coast or the Midwest. Gradually disagreements emerged between the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), which tried to prove their allegiance by conforming to the administration, and those who believed that remaining passive was wrong. The American government was taking advantage of these disagreements: based on polls, it was releasing the “loyal citizens” to find jobs in the Midwest and East Coast; while sending the “troublemakers” to the Tule Lake camp in California. Those living in the camps were feeling like prisoners of war or convicted inmates. In fact they were not wrong to feel as such since the barbed wires surrounding the camps, watch towers and armed guards were reinforcing the feeling of being a prisoner of war. Guards were ordered to shoot anyone who tried to leave the camp without permission or did not heed to the warning to stop. In 1942 an investigation was started concerning this order. An immigrant had been shot by a soldier on patrol. The investigation revealed that the person was shot from the front. It was not a case of not heeding to the warning to stop as was claimed by the guard.

Consequently, as sites where constitutional citizenship rights were suspended the Internment Camps were the manifestations of a government mentality in America’s recent past the effects of which still continue today. The reparation of damages inflicted by this mentality also harbors a unique experience in terms of coming to terms with the past and practices of official apology.

What were the political relations that led to the Executive Order which deprived the Japanese Americans from their constitutional right to fair trial? The answer to this question can be found in the report prepared by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) established by Congress in 1980. The Commission reached its decision after hearing the testimonies of 750 witnesses in its sessions. According to the report, the Executive Order was carried out not due to military necessities but was motivated with “racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership”. The Commission report pointed at the difference of practices implemented in Hawaii as it provided further proof of this fact: In Hawaii, only 1 % of the Japanese Americans, who constituted 35 % of the Hawaiian population, were detained.

In line with the Japanese American Claims Act passed by Congress and signed by President Harry S. Truman in 1948, it was decided to settle the property loss claims and pay reparations. A budget of $38 million was appropriated to settle the claims of 23,000 people for damages totaling $131 million. In 1952, racial and ethnic restrictions in immigration and citizenship acts were abolished, and immigrants including Japanese Americans received the right to become naturalized as US citizens.

With their socioeconomic achievements the children of immigrants had joined the ranks of middle class by 1960s. This new generation -surely also with the effect of the Vietnam War- started to question the previous generation’s conducts in the Second World War. They were criticizing their parents for remaining passive and not struggling enough for their civil rights. While they tried critically to account for the past they also placed more emphasis on their ethnic origins. The struggles were panning out: Japanese Americans attained their first democratic gain on February 10, 1976 with President Gerald Ford’s Proclamation 4417. In the aforementioned proclamation President Ford described February 19, 1942 as a sad day in American history. An unlawfulness of the past was officially acknowledged by the authority. With the following words President Ford declared that the Executive Order was repealed:

“I call upon the American people to affirm with me this American Promise -that we have learned from the tragedy of that long-ago experience forever to treasure liberty and justice for each individual American, and resolve that this kind of action shall never again be repeated.”

Despite the official discourses of President Ford, it would take as long as 12 years for the reparation package to be prepared. In 1980 President Jimmy Carter signed the law for the reestablishment of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) in Congress. The Commission Report published in June 1983 made five recommendations to the Congress: 1) that Congress pass a joint resolution offering a public apology; 2) that the President pardon those convicted of curfew violations and review other wartime convictions based on discrimination due to race or ethnicity; 3) that Congress direct agencies to review applications for restitution of positions, status or entitlements lost as a result of wartime events; 4) that Congress appropriate monies to establish a foundation to address the nation’s need for redress, including a fund for educational and humanitarian purposes beyond individual reparations; and 5) that Congress establish a fund to provide redress of $20,000 to each of the remaining 60,000 surviving persons of Japanese ancestry incarcerated during the war. All these recommendations were legislated with the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. In 1980s Japanese Americans were a politically inactive minority that constituted less than 1 % of the entire population. Furthermore, in terms of reparations they were divided between the legislative and judicial courses of action. Moreover they were demanding a total of 1.25 billion dollars in reparations at a time when the federal budget deficit had reached record-high levels.

There was a serious vein of opposition against reparations. Especially certain veteran groups were opposed to the reparations. On the other hand, groups such as the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion never officially opposed the reparation act. Though they did not lobby in favor of the law, in their meetings they passed decisions supporting reparation. The reason behind this was the Japanese Americans who were stationed in the North Africa and Europe front and in the Pacific working in intelligence units. These veterans who served while their families were in the concentration camps convinced their colleagues with regards reparations. The sole group opposing the law was the Americans for Historical Accuracy based in California and led by historian Lillian Baker. Claiming that they are against the distortion of American history and are working to this end, the group organized letter-writing campaigns along with certain demonstrations and testified at the Congress sessions. On the other hand, the fact that senators and representatives were able to cast their votes freely regarding the law and that parties did not apply coercion was an important factor in the creation of the reparation package. Japanese Americans did not stop striving to pass the reparation package. They were getting in contact with other organizations such as Asian American groups and civil rights groups. They were making use of these groups’ contacts, members, resources and political expertise in order to put pressure on the Congress.

Finally the Civil Liberties Act was signed in 1988 by President Ronald Reagan and the path to reparations was opened. On December 7, 1991 that marked the 50th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack, President George H. W. Bush wrote a letter of apology. On September 27, 1992 he also signed into law the Civil Liberties Act Amendments of 1992, appropriating an additional $400 million to ensure all remaining internees received their $20,000 redress payments. Surviving detainees of the camps received checks of redress payments along with a letter of apology signed by President Bush. The following words towards remembering and confronting the past are from the formal apology issued by Bush on behalf of the US government in 1991:

“In remembering, it is important to come to grips with the past. No nation can fully understand itself or find its place in the world if it does not look with clear eyes at all the glories and disgraces of its past. We in the United States acknowledge such an injustice in our history. The internment of Americans of Japanese ancestry was a great injustice, and it will never be repeated.”

Following Bush’s letter, President Bill Clinton also wrote a letter of apology on October 1, 1993. Along with letters of apology and reparation payments another process was carried out in the USA in line with coming to terms with the past. It was decided to appropriate funds from the 2001 budget to transform the Internment Camps into “national historic sites” and preserve them as landmarks of remembrance:

“Places like Manzanar, Tule Lake, Heart Mountain, Topaz, Amache, Jerome, and Rohwer on which the detainee camps were set up will forever stand as reminders that the American nation failed in its most sacred duty to protect its citizens against prejudice, greed, and political expediency.”

It cannot be denied that all these activities of apology and confrontation with the past had a positive effect in the USA especially during the post 9/11 processes. Such that, American-citizen Muslims -though there was a certain sense of threat in effect- were treated with the lessons learned from experience. The term “never again” has indeed been actualized in real life.

During their rule Nazis killed approximately six million people, the vast majority Jews. On November 20, 1946 the International Military Tribunal was established by the allies in Nuremberg and the leading figures of the Nazi rule were tried and punished –with sentences including capital punishment. These military trials though constituted a legal basis or a starting point for processes of coming to terms with the past were not enough for a social and general confrontation. After the tribunal, Adolf Hitler and his associates and followers became the focus of fascism. Atrocious operations of the Nazi regime were relegated to Hitler, while the German society was being spared as innocent citizens led astray by ideologies. These differentiations were maintained for a long time: Auschwitz trials held in mid-1960s in Frankfurt and again the Eichmann trial held in 1961 in Jerusalem would personalize the crimes of the past and sustain the narrative of “singular criminals among decent Germans”.

In Germany during the first years after the war the Nazi past did not want to be remembered. Nevertheless, it was not possible to erase the societal memory completely. Therefore the processes of forgetting and remembering were operating intertwined with one another. In this framework, the word “genocide” was adamantly and skillfully avoided in public discourses like commencement speeches at the universities, in its stead terms that mitigated historical facts such as “race mania” and “mass killings” were used, and the word “Jewish” was rarely mentioned. It was acknowledged that certain crimes were committed in the past but it was asserted that these crimes were not genocide as alleged by some.

The period of 1945-49 went down in history as a time when the past was discursively suppressed. The suppression of the past brought along an exemption from collective responsibility. Many factions from the people in the lowest social ranks to the top level political representatives were saying that the actual victims were not the Jews but on the contrary themselves. Ignorance was claimed regarding the gas chambers and death trains, thereby trying to elude the feeling of social responsibility. Having the Germans visit the concentration camps, and the preparation and circulation of documentaries on the subject invalidated the excuse of “ignorance” before long. The German public had to solemnly confront the past: the facts were plainly manifest in the concentration camps without a shadow of doubt.

The 1960s marked the beginning of an era when the societal silence in Germany gradually started to dissipate. Both domestic and international democratic pressures were now mandating the suppressed past to be laid out on the table. Contrary to Federal Germany’s official politics of forgetting, the socialist East Germany constantly kept its Nazi past on the agenda and asserted that the political personnel in the West were Nazi dregs. Though it “discarded” its Nazi past by externalizing and pinning it completely on the West, the fact that East Germany could not hinder the underhanded reproduction of the Nazi mentality would only be seen after the Berlin Wall came down and the two Germanys united. Emergence of the 1968 youth movements had an impact in Germany that begot a more significant factor with regards the questioning of the Nazi past. The young generations were ethically condemning the previous generations, creating discourses for a genuine and real confrontation, and striving to uncover the truths. Tribunals were opened again. Truths were being spoken candidly, the denied crime of genocide was being acknowledged. Billions of Marks were paid in reparations. Monuments reminding the past were erected in every region. Certain days of the year were earmarked for ceremonies to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust. In coming to terms with the past, another important development took place -at a completely unexpected moment- and brought some comfort to the victims: Federal Germany Chancellor Willy Brandt’s gesture of apology before the monument to the victims of Warsaw Jewish Ghetto on December 7, 1970 went down in history as a kind of turning point in coming to terms with the past. Apology could be made not only verbally but also physically. As a matter of fact, Brandt kneeled before the monument and apologized from the victims through his body. This gesture of extremely high symbolic value was actually meant not only for those in Warsaw but for all Jews who lost their lives in the politics of “Final Solution”. The representation had long exceeded the boundaries of an individual body: Willy Brandt’s body transformed into the representational body of Germany.

Germans’ politics prior the Second World War had taken on the following course: ghettos were established in all invaded territories whereby Jews were segregated from the society and stripped off their constitutional citizenship status. As a matter of course, resistance networks were organized against the Nazi rule’s domination politics nourished by colonialism. Between 1941-43 Jews living in the ghettos had created close to a hundred resistance groups. The most resounding resistance organized by the aforementioned groups was the resistance in Warsaw Ghetto. Until the summer of 1942, the Warsaw Ghetto was one of the isolation areas filled with around 500 thousand people. In the summer of 1942, around 300 thousand Jews were taken from the ghetto and sent to the extermination camp in Treblinka. Word reached the ghetto that the people sent to the camp were massacred and this news created a certain wave. Also with the duress of this news, a group of mostly young people led by the 23 year old Mordecai Anielewicz founded the Jewish Combat Organization (ZOB). The organization issued a proclamation calling for the Jewish people to resist going to the railroad cars. On January 18, 1943 the German army started a second deportation campaign but was met with the armed resistance of the organization. After violent clashes lasting a few days, the Germans had to retreat. Repelling the Germans boosted the morale of the resistance. On April 19, the German soldiers and the police corps organized a new operation to evacuate the people living in the ghetto. The resistors, who were numbering around 750, were able to hold out in the ghetto for about a month and on May 6, 1943 the resistance was quashed. Around 56 thousand Jews were taken captive. Seven thousand of the captives were executed by fire squads, the rest were sent to execution camps. In the slaughter of Jews across Europe, Poland was engraved in the Nazi rule’s crime log as a country of grave importance. Therefore, in line with the discourse of coming to terms with the past it was no coincidence that Willy Brandt chose the Warsaw Ghetto.

Willy Brandt spent a part of his life running away from the Nazi rule’s exile and execution politics. Born as Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm, Brandt joined the Socialist Youth in 1929, the German Social Democrat Party in 1930 and later on the Socialist Workers Party, and practiced politics actively during these years. In 1933 in order to escape the Nazi persecution he took shelter in Norway as a political refugee, and adopted the pseudonym Willy Brandt not to be caught by Nazi agents in Norway. In 1939 Brandt was arrested in Norway by German troops but was not recognized as he was wearing a Norwegian uniform. Upon his release he escaped to Sweden where he lived until the end of the war. He continued to use his pseudonym Willy Brandt after the war as well.

The secret to the political influence of Willy Brandt’s kneeling should be sought in his commitment to democratic values and the fact that he personally suffered from fascism, and moreover was not involved in the crime. His political character made it impossible to slander this symbolic gesture of apology as a duplicity or political scheme. The gesture of apology was also pertinent to his Eastern Politics (Ostpolitik). It would be cruel to construe it as an apology made with pragmatic motives, or more precisely as an “instrumentalized” apology. Besides, in Brandt’s eyes the two processes -Eastern Politics and apology- complemented one another. Let us expand on the Eastern Politics to better understand the affirmative essence of this genuflection.

Through his Poland visit, Brandt wanted to ease relations between the Eastern and Western blocks that emerged in Europe in the aftermath of the Second World War. The Potsdam Agreement signed after the war had ceded to Poland the pre-war German territories such as East Prussia, West Prussia, Pomerania, Brandenburg, Silesia and Upper Silesia. It was guaranteed to Germany that there would be no loss of territory without a peace treaty. Germans living in the aforementioned territories immigrated to Germany. The Poles living in Poland, which was incorporated into the Soviet territory, were settled on the evacuated lands. Until the Eastern Politics, pioneered by Willy Brandt, the Federal Republic of Germany had not abdicated its claim to sovereignty on these territories. “Surrender is Treason” (Verzicht ist Verrat) was the line adopted by mainstream politics since the Christian Democrats in 1960s to the Social Democratic Party of Germany which Willy Brandt was a member of.

In 1961 the Berlin Wall was built. American President Kennedy had reacted favorably to the building of the wall as a process mitigating the Soviet-American tension. Accordingly, from now on the zones of influence between the two “super powers” would be evident. All these developments based on the separation of East and West impelled Brandt, who was the Mayor of Berlin in 1961, to deliberate on the necessity of a different approach. Following the 1969 elections, the Social Democratic Party and the Free Democratic Party formed a coalition government. In his June 17, 1970 speech before the German parliament (Bundestag) as Chancellor, Willy Brandt made the following remarks regarding Eastern Politics:

“If we want European borders to lose their divisive function over time in a historical process, then we have to acknowledge the existing borders first, de facto and politically. The objective of Eastern Politics was to institute German foreign policy on a realistic ground. Through this politics it was aimed to improve relations with primarily Eastern Germany and also the Eastern Bloc countries such as the Soviet Union, Poland and Czechoslovakia. Brandt’s visit to Warsaw intended to launch the process of rapprochement between Germany and Poland. In the Treaty of Warsaw signed on December 7, 1970, it was decided that both parties would commit themselves to nonviolence and recognize the existing Oder Neisse border. Brandt’s Eastern Politics was welcomed by the international public opinion. Surely there was also opposition to this politics. Conservative circles close to the Christian Democrats and associations organized by ethnic German migrants from East Germany were opposing Brandt. Meanwhile, Günter Grass and other intellectuals close to Brandt were among the most important supporters of Eastern Politics.”

After the Treaty of Warsaw was signed, Willy Brandt visited the Ghetto Monument with a wreath that bore the black, yellow and red colors of the German flag. After laying the wreath on the monument, in a moment unexpected by anyone, he dropped to his knees on the wet stones of the monument. He respectfully folded his hands before him and looked at the monument in silence with his head held a little low. The impact of this gesture that shook not only those present but the entire world was summarized by one who had participated in the Warsaw resistance:

“I saw Willy Brandt kneel before the Warsaw Ghetto monument. This is what I felt at that moment: I no longer have hatred inside! He knelt down and raised his people. Brandt’s gesture had created a shock effect among the people present. At first no one was able to make sense of this act. It was not a predetermined action. There were even some who thought he fainted. While some people interpreted the gesture as a sincere act others questioned its sincerity. For years Brandt was subjected to questions on the reason and motivation behind his act. Perhaps due to this situation, in his book titled My Life in Politics published in 1989 he mentioned this gesture again. Before his visit to the Warsaw Ghetto, Willy Brandt had spent the night in the Wilanow Castle bombed by Germans. He had spent a sleepless night in this castle that still bears traces of the war. In the book Brandt explained that night and his memories of kneeling as follows:”

“I have often been asked what the idea behind that gesture was: had it been planned in advance? No, it had not. My close colleagues were as surprised as the reporters and photographers with me (…) I had not planned anything, but I had left Wilanow Castle, where I was staying, with a feeling that I must express the exceptional significance of the ghetto memorial. From the bottom of the abyss of German history, under the burden of millions of victims of murder, I did what human beings do when speech fails them.”

Brandt’s Eastern Politics and symbolic genuflection were received quite favorably in many other countries and especially the USA. Time magazine put Brandt on the cover of its January 4, 1971 issue as the “Man of the Year”. Meanwhile reactions within Germany were mixed. According to a Der Spiegel survey at the time, 41% of the participants found the “Kniefall” appropriate while 48% thought it was excessive. It was noteworthy that the youth and the elderly supported Brandt more than the middle-aged. Eastern Politics was criticized by especially the right wing. Bild newspaper saw no harm in publishing the letter of a housewife by the name Erna Hannebauer: “With what right are you giving away one fourth of Germany without receiving any concession in return?” Newspaper’s editor in chief Peter Boenisch was also criticizing Willy Brandt in a sharp tone: Catholics know that a person kneels only before God. However, a socialist probably separated from the church comes from the West and kneels down. This genuflection moves the people. Fine but wonder if this genuflection would move the victims of Stalinism as well?

Christian Democrat Parties (CDU and CSU) openly opposed Eastern Politics and claimed that it was unconstitutional. Despite all the reactions from the right wing, an influential and steadily growing minority in CDU was convinced that for the normalization of relations with the East and specifically with Poland, the border arrangement was inevitable. Willy Brandt’s Eastern Politics brought a de facto end to the existing hostility between the two countries. Brandt’s genuflection at the Warsaw Ghetto increased the prestige of both Eastern Politics and Germany’s foreign policy. Willy Brandt was granted the Nobel Peace Prize in 1971 for his works in the service of peace between Eastern and Western blocks.

Beyond being a sensational event with wide media coverage, Willy Brandt’s genuflection was an action that essentially opened a new era in the German societal memory and identity and transformed the Germans’ ways of confronting and coming to terms with the Nazi past. The apology had both a personal and political quality. It was a courageous act that was undertaken also in the name of the people who could not kneel before the past. In time, Willy Brandt’s genuflection became a significant symbol conveying the desire to come to terms with the past both in Germany and in international politics.

German state authorities apologised on several occasions from Israel and from the Jews, and Germany has paid extensive reparations, including nearly $70 billion to the state of Israel and $15 billion to Holocaust survivors.

“Kniefall angemessen oder übertrieben?”, Der Spiegel 51: 27, 1970,

“The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising”, US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Adam Krzeminski, “Der Kniefall”, Point. Portal Polsko-Niemiecki, Deutsch-Polnisches Portal.

Orjinal metin için: Polityka 49.

Alexander Behrens, “‘Durfte Brandt knien?’ – Der Kniefall und der deutsch-polnische Vertrag”, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Online Akademie, 2010,

Elazar Barkan, Alexander Karn, “Group Apology as an Ethical Imperative”, Taking Wrongs Seriously: Apologies and Reconciliation içinde, Elazar Barkan ve Alexander Karn (der.), Stanford: Stanford University Press, 3-30, 2006.

Markus Kornprobst, Irredentism in European Politics: Argumentation, Compromise and Norms, Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Mithat Sancar, Geçmişle Hesaplaşma: Unutma Kültüründen Hatırlama Kültürüne, İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2007.

Ruti Teitel, “The Transitional Apology”, Taking Wrongs Seriously: Apologies and Reconciliation içinde, Elazar Barkan ve Alexander Karn (der.), Stanford: Stanford University Press, 101-114, 2006.

Valentin Rauer, “Symbols in Action: Willy Brandt’s Kneefall at the Warsaw Memorial”, Social Performance: Symbolic Action, Cultural Pragmatics, and Ritual içinde, Jeffrey C. Alexander, Bernhard Giesen ve Jason L. Mast (der.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 257-282, 2006.

Willy Brandt, My Life in Politics, New York: Viking, 1992.

In settler states such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, USA and Argentina the fundamental issue for the “natives” has been to preserve their existing identities against the assimilation policies of the colonialists. In course of establishing political sovereignty, these states that practice colonialism in parallel with settler policies have resorted to the assimilation of native “elements” on the lands they have invaded. Natives have been subjected to assimilation politics in various forms, which led to a vast accumulation of rights violations. The acts carried out by settler colonialist states are both in violation of present-day criteria of morality and justice and also constitute an important problem with regards the dominant national identity. The collective feeling of guilt begotten by assimilation politics was at first tried to be overcome through the rationalization of past actions. However in the eyes of many groups -taking into consideration the various inequalities targeting the natives- this attitude fell short of being sustainable. How the practices of the past are to be confronted today when these practices contradict the current criteria of morality and conscience constitutes yet another crucial issue. In states founded on settler colonialism mentality, contemporary identity discussions continue to be among the fundamental problems. One of these countries where identity discussions run parallel to processes of coming to terms with the past is Australia, a state that implemented cruel assimilation politics especially on children.